How Second-Hand Fashion is Shaping Sustainability

As Copenhagen’s thrift scene grows, second-hand fashion highlights Europe’s push for sustainability while exposing the hidden health and environmental costs of fast fashion.

Sprawled over the streets of Copenhagen, thrift shops spill over with racks of patterned dresses, retro jackets, and jeans. For many, browsing second-hand isn’t just about style, but part of the city, and the EU’s growing commitment to sustainable living.

On average, textiles have the third highest impact on water and land use, and the fifth highest in terms of raw material use and greenhouse gas emissions, according to a 2020 report by the European Environmental Agency (EEA).

“The moment I found out about the impact, I quit [buying new clothes] immediately,” says Ioana Voica, the shopkeeper of Quirky Lane, a thrift shop in København K. “I couldn’t stop thinking about it.”

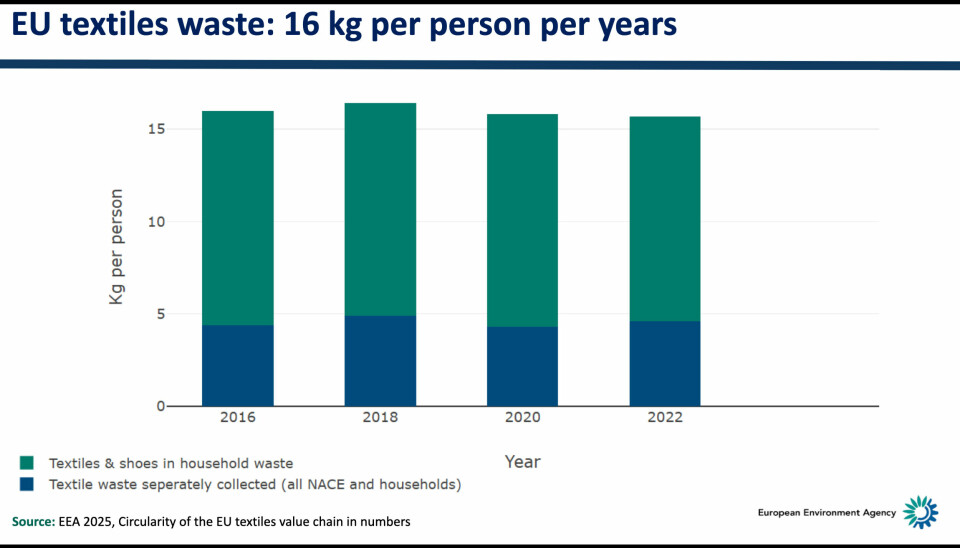

In 2022, each person in the EU consumed on average 19 kg of textiles—the weight of over two carry-on suitcases—a two-kilo increase from 2020.

“Myself, I buy all my clothes second-hand,” Voica adds, who started as a second-hand shopper before working at Quirky Lane.

The second-hand clothing scene has boomed in Copenhagen over the past years, with more than 80% of Danes over the age of 16 having visited a Red Cross shop in 2024.

Denmark now sits in eighth place worldwide in terms of thrift market value, according to a study published by Public Desire, with the U.S. and the U.K. leading the way. This underscores Denmark’s strong commitment to second-hand fashion despite it holding the smallest population in the top 10.

The Red Cross Denmark alone generated a revenue of DKK 312 million last year, with 260 shops in operation.

While the U.S leads the way in second-hand fashion shopping, they do not collect textile waste separately and lack eco-design or extended producer responsibility schemes for clothing.

“This is an incentive to generate less waste and handle the waste generated better, in terms of reusing and recycling more,” says Lars Mortensen, a textiles expert from the EEA, on the EU’s new Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) schemes.

Although second-hand clothing helps keep textiles out of landfills, Mortensen says the bigger challenge is stopping waste before it’s created. He recommends buying fewer items, choosing higher-quality pieces, using them for longer, and repairing them when needed.

The Health Risks

Above the environmental issues, fast fashion and the overproduction of textiles also pose health concerns, with heavy dyes and chemicals affecting consumers and producers alike.

“I was having sweating problems,” says Voica. “The chemicals that are used are super dangerous, not only for the environment, but also for us.”

Voica’s case is not in isolation, with flight attendants at Alaska Airlines reporting a surge in cases of sore throats, coughing, shortness of breath, itchy skin, rashes, hives, irritated eyes, loss of voice, and even blurred vision nearly doubling, after new uniforms were introduced in 2011.

Chemicals in dyes made with benzidine, optical brighteners, solvents, and crease-resistant agents that release formaldehyde are examples of substances linked to health risks.

“Now I only buy natural fibers, but still if the clothes are dyed with strong stuff, I can feel it—I get sweaty and itchy,” Voica says.

The Center for Environmental Health (CEH) detected high levels of bisphenol A (BPA)—a hormone-disrupting chemical that can be absorbed through the skin—in everyday items like socks, sports bras, and athletic shirts.

While there are no federal standards for what can be put in clothing for adults in the U.S., the EU has banned more than 30 substances for use in fashion. These include lead, chromium, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which can also leach out during washing.

Next Steps

Much of the responsibility for waste management still falls on consumers, with policies often focused on providing information—such as eco-labels—rather than making circular options more affordable and attractive.

However, new policies like the EU’s Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation will introduce rules for clothing sold in the bloc, setting requirements for recycled content, durability, and repairability, increasing pressure on the producer, rather than the consumer.