The salary bridge: commuting between Sweden and Denmark

COPENHAGEN, 15 Sep — Denmark heads into a decisive political year with local elections in November and a general election due by 2026. At the top of the agenda: a housing crisis that has pushed rents and prices to some of the highest in Europe, straining young people, families, and even the people across the Øresund in Sweden.

The housing crisis is set to be the biggest problem, and it will dominate the campaign. For decades, governments have chosen not to build enough affordable housing or regulate private rents. Local politicians can’t really do much, most of the legislation sits at Christiansborg.

ROLE OF SWEDEN

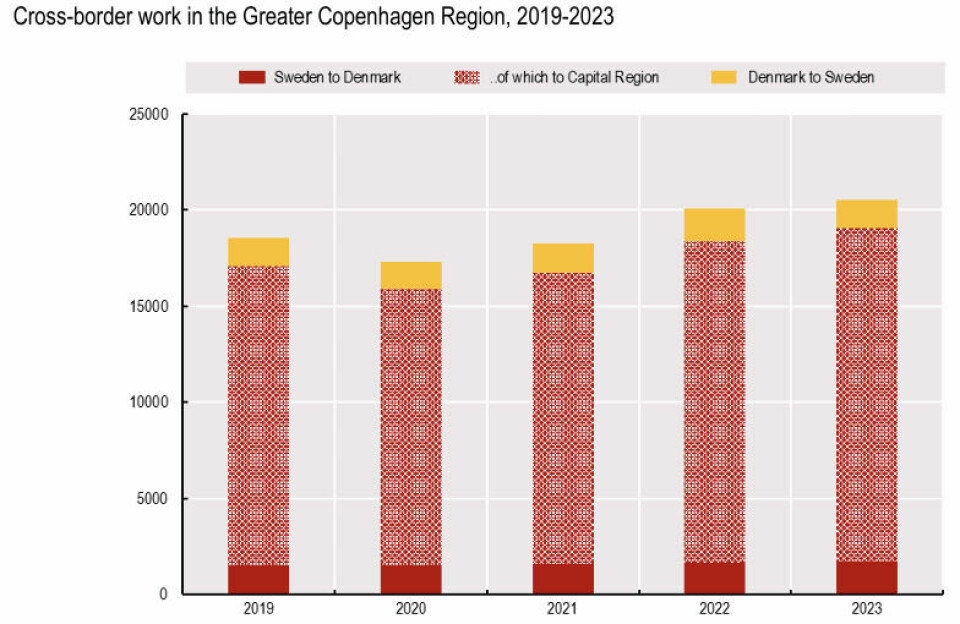

The struggle over affordability is not only a Copenhagen problem. According to a 2024 OECD report, each day more than 19,000 people cross the Øresund Bridge from Sweden to work in Denmark’s capital, 60 percent of whom live in Malmö.

This makes them part of the city’s economic heartbeat— and they too are exposed to navigating the same pressures of wages, housing, and cost of living from across the border.

Therefore, the political debate in Copenhagen is not abstract. It is part of their daily routine. These people are drawn by Denmark’s higher wages and job opportunities while benefiting from Sweden’s lower living costs.

The average hourly wage for Swedish commuters in Copenhagen exceeds DKK 33 (EUR 4.46), compared with SEK 42 (EUR 3.55) in southern Sweden—a quarter increase in income.

Meanwhile, Copenhagen’s job vacancy rate stood at 3% in early 2024, three times higher than in Scania, southern Sweden.

Currency trends have only reinforced this pull: the Swedish krona has steadily depreciated against the Danish krone since 2012, making Danish salaries even more attractive. These things have made the bridge a lifeline for thousands.

OPPORTUNITIES VS CHALLENGES

Yet the cross-border journey—often close to two hours each way—is more than just an economic calculation. For commuters, it’s a balance of opportunity and sacrifice.

For IT consultant Markus Jonsson, the chance to work in Copenhagen was about seizing opportunity: “I was contacted by a company in Copenhagen before anyone else did, the job seemed interesting and felt like a good opportunity,” he says.

Nuri, who works in sales, points to the financial benefits: “The salary is better here compared to Sweden, and the cost of living in Malmö is cheaper than Copenhagen.”

Emma Bellstam, who works as a barista, sees the cross-border experience to invest in her future, seeing her job as a stepping stone “It helps me establish myself in Denmark with a CPR number and a bank account, so I can apply to larger companies. Copenhagen also has more opportunities in my field of animation and design—it’s a bigger market than Malmö,” she says.

But these opportunities come at a cost. Markus admits the daily journey is time-consuming: “It eats up my day—travelling takes two hours every day. It’s probably time I could have saved if I worked closer.” Still, he shrugs off the inconvenience, noting others travel even longer and further.

For Emma, Danish bureaucracy has slowed her progress: “Getting into the system has been tricky,” Emma sighs. “The biggest issue has been with getting a CPR number and a bank account. I’m still, after months, waiting for my bank account. Luckily, I was able to get my salary as soon as I got my CPR number, but that also took about 2 months.”

And for business consultant Ola Ekvall, the daily journey is proving a physical and emotional struggle. Winter delays, make the commute “very stressful” and take “a heavy mental toll,” he says.

BRIDGING GAP

Beyond wages and jobs, the Malmö–Copenhagen connection highlights deeper questions of identity and integration. The relationship between Copenhagen and Malmö is a bit strange. Malmö really wants to get closer to Copenhagen, but Copenhagen does not always want the same. Malmö is seen as a city with higher levels of poverty, crime, and discrimination.

There are plans to extend the metro under the sea to make commuting easier, reflecting a desire to strengthen ties. But national politics often get in the way, as the divide between the two cities continues to grow.

In the meantime, the Øresund Bridge continues to carry tens of thousands back and forth each day. While national policies stall, individuals find their own ways to bridge the gap—some navigate the daily struggles of commuting, others seize the opportunities offered by the EU and Schengen.

This story is for an international audience interested in cross-border economic opportunities and urban commuting challenges. It could be published in the Europe section of the Financial Times for readers who follow European economic and social trends.